Sepsis is one of the blood-borne diseases, mainly caused by bacterial or fungal infection from the blood stream. In the context of COVID-19, which claims the 7 milions of life so far in total,1 sepsis claims more number (~11 M) every year, taking up to 20-30 % of the mortality.2 This means that 1 our of 5 people die because of sepsis.

There are many types of pathogens (bacteria or fungus) that cause blood stream infection. With the known identification of sepsis causing pathogens and specific antibiotic treatment, its therapeutic efficiency could be higher than 80%.3 For example, Rifaximin for E. coli infection or penicillin for Staphylococcus aureus infection. However, it is extremely difficult to identify the pathogen in the blood, which makes sepsis one of the most important diagnostic and therapeutic challenges from the blood stream infection.

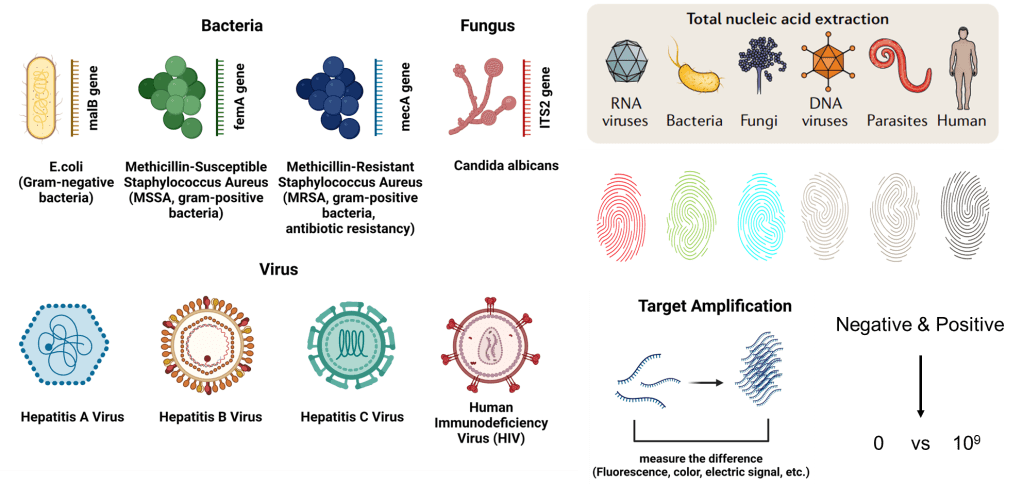

All living creature possess genetic code made up of either DNA or RNA. Their genetic sequence is unique to themselves much like a fingerprint. By crafting primers tailored to target specific sequences, we can pinpoint particular pathogens. Another method employed is nucleic acid amplification, amplifying the target DNA to over a billion copies, enhancing the differentiation between positive and negative samples. PCR stands out as the most renowned technology for this purpose.

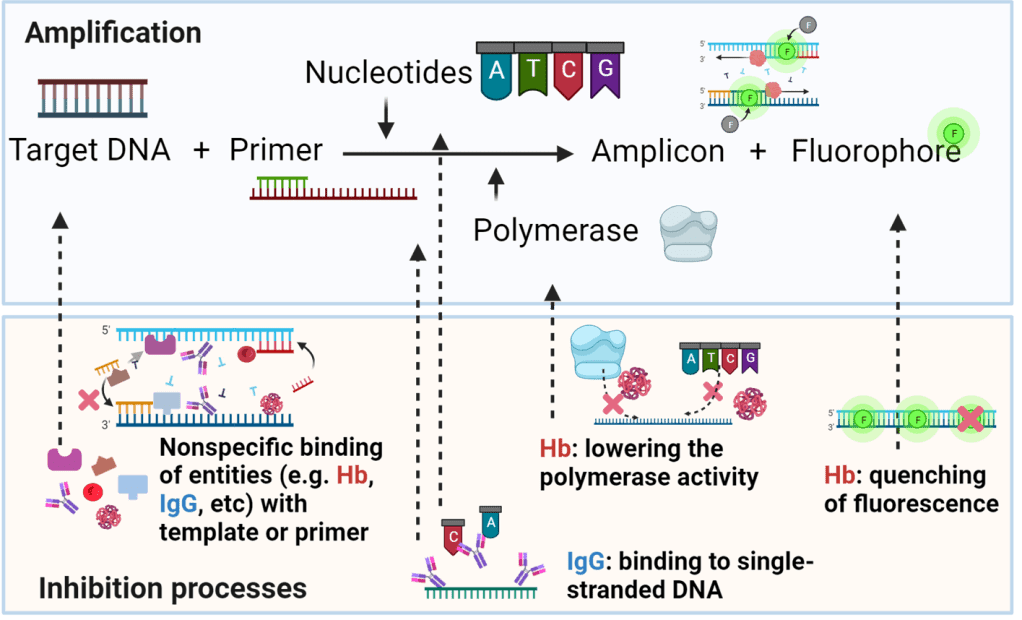

In blood samples, stuff like proteins and hemoglobin can mess up PCR reactions. They stick to the reaction ingredients and slow things down. To fix this, we use purification techniques. We attach the DNA we want to silica or magnetic beads, which grab onto all the junk in the sample. Then we wash away the junk and get back our clean DNA. This ensures that when we run the PCR reaction, we’re working with pure DNA, giving us accurate results.4

Purification methods can run into trouble when dealing with target DNA in blood because it’s often found in really low amounts. For example, samples with respiratory viruses like SARS-CoV-2 might only have 100-1000 copies per tiny drop of sample. But in cases of sepsis, it can be even worse, with maybe just 1 copy per entire milliliter, which is a lot less. In situations like these, the process of sticking the DNA we want to silica or magnetic beads and then washing away the junk isn’t as effective because there’s just too much junk compared to the tiny amount of DNA we’re interested in.

Imagine you have a haystack with some magnetic dust mixed in. You use a big magnet to pull out the magnetic dust from the haystack. When you wash away the hay, the magnetic dust stays stuck. So, when you remove the hay, you’re left with just the magnetic dust. But if there’s too much hay compared to the amount of magnetic dust, you might not get all the magnetic dust out. This shows that getting pure DNA for PCR reactions becomes really tough in these situations.

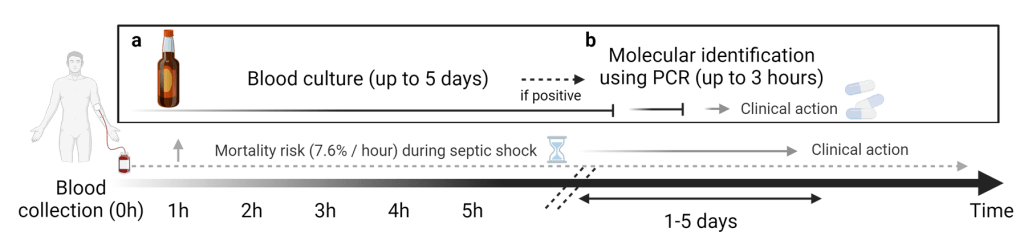

To address this challenge, the current gold standard method relies on blood culture, which boosts the number of live pathogens to a level where they can be detected. By growing the pathogens in the blood sample, we get a lot more of them, making purification easier. It’s like having a ton of magnetic dust left over after washing the haystack, so there’s plenty to collect during purification. This process typically involves three main steps:

- Increasing the amount of pathogenic DNA through culture, which takes up to five days.

- DNA extraction and purification, requiring approximately 1 hour.

- PCR, which takes about 1.5 hours for amplification and detection.

Blood culture, unfortunately, is a slow process, often taking up to five days to provide results. This extended waiting period is particularly worrisome because the risk of mortality rises by 7.6% every hour once septic shock begins. Essentially, there’s a notable mismatch between the time needed to identify pathogens and the critical window, referred to as the “golden time,” during which life-saving interventions are most effective.5

In clinical settings, doctors often resort to prescribing a wide range of antibiotics without knowing the specific pathogen causing the bloodstream infection, aiming to save lives in urgent situations. While this approach is necessary, it creates a serious issue. For example, if a pathogen is resistant to one of the antibiotics given, it gains an advantage, multiplying while other strains are killed off. This results in only the antibiotic-resistant pathogens surviving. Essentially, this process leads to the replacement of entire populations with antibiotic-resistant strains. Consequently, the rise of antibiotic resistance and the spread of superbugs pose a significant threat, potentially leading to future pandemics. Ultimately, if this trend continues, there may come a time when no antibiotics are effective even against simple infections.

Developing a new antibiotic is a complex and time-consuming process that demands substantial investment. Bacteria, such as E. coli, have remarkably fast growth rates, doubling in number every 15-20 minutes. Their replication process is analogous to transcribing a book, but with a significant distinction: it’s not as precise as a printing process. Instead of copying perfectly, bacteria essentially write characters one by one, which introduces the possibility of errors. Although the error rate is incredibly low, estimated at around 1 mistake per 100 million to billion base pairs, considering their rapid reproduction and doubling time, these errors can accumulate over time. This accumulation can lead to the emergence of new variants, including those with antibiotic resistance.

Once bacteria develop resistance to antibiotics, human actions inadvertently aid in their spread. The extensive use of antibiotics creates selective pressure, promoting the survival and reproduction of resistant bacteria. Consequently, many efforts and investments in antibiotic development become futile, as the emergence of resistant strains undermines the efficacy of newly developed antibiotics. Therefore, despite significant resources allocated to antibiotic research and development, the rapid evolution of antibiotic-resistant bacteria often renders these efforts ineffective.

To tackle the challenge of antibiotic resistance, researchers are pioneering innovative approaches using advanced technologies. One such initiative involves harnessing artificial intelligence (AI) to develop new antibiotics. Using AI algorithms, scientists have identified a promising group of compounds capable of targeting and eliminating drug-resistant bacteria.

Reference

- https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/cases?n=c

- https://www.who.int/news/item/08-09-2020-who-calls-for-global-action-on-sepsis—cause-of-1-in-5-deaths-worldwide

- Kumar, A., Roberts, D., Wood, K. E., Light, B., Parrillo, J. E., Sharma, S., … & Cheang, M. (2006). Duration of hypotension before initiation of effective antimicrobial therapy is the critical determinant of survival in human septic shock. Critical care medicine, 34(6), 1589-1596.

- Lim, J., Zhou, S., Baek, J., Kim, A. Y., Valera, E., Sweedler, J., & Bashir, R. (2023). A Blood Drying Process for DNA Amplification. Small, 2307959.

- Ganguli, A., Lim, J., Mostafa, A., Saavedra, C., Rayabharam, A., Aluru, N. R., … & Bashir, R. (2022). A culture-free biphasic approach for sensitive and rapid detection of pathogens in dried whole-blood matrix. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 119(40), e2209607119.